From Lake of the Clouds to Isle Royale, discover how a failed split in Earth’s crust created some of Michigan’s most iconic landscapes.

Photo: The richly colored sandstone cliffs and sculpted archways of Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore reveal layers of sediment laid down as ancient inland seas filled the Midcontinent Rift basin. Photo by Alexeys

If you’ve ever been to Lake of the Clouds, Isle Royale, or the sacred Gichi-Gami herself, Lake Superior, you’ve witnessed the remains of a billion-year-old geological upheaval that nearly tore North America in half.

Beneath these iconic Michigan landmarks lies the Midcontinent Rift, a vast scar from an ancient time when molten rock surged through the Earth’s crust, shaping the rugged beauty of the Upper Peninsula. Though the rift ultimately failed to split the continent, it left behind the dramatic landscapes we know and love today.

What Is the Midcontinent Rift?

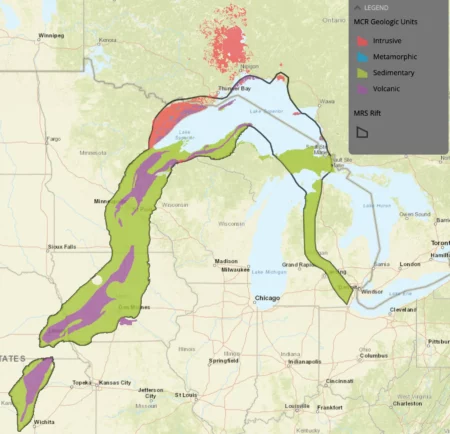

Roughly 1.1 billion years ago, long before dinosaurs roamed and well before Michigan existed in any recognizable form, a massive crack began forming in what is now the middle of North America. Known as the Midcontinent Rift System (MRS), this tear stretched some 1,200 miles from what’s now Kansas up through Lake Superior and down toward Ohio.

Fueled by rising magma from deep in the Earth’s mantle, the rift was an attempt by the planet to split the continent apart. Geologists believe this rifting event was connected to the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia (1.26–0.90 billion years ago), which predates the more familiar Pangaea (200 million years ago). While Pangaea eventually fractured into today’s continents, Rodinia’s dismantling left behind geologic scars, including the Midcontinent Rift.

How It Shaped Lake Superior

Although the rift failed to fully split the continent, it left behind an enormous and deep structural weakness. Lava welled up through the rift, forming thick basalt layers. Over time, these were buried by sediment, then carved by glaciers into the basin we now know as Lake Superior.

Today, Lake Superior’s vastness and depth reflect the ancient rift’s imprint. It’s not only the largest freshwater lake by surface area in the world, but it’s also among the deepest and geologically oldest.

Key Places Where the Rift Emerges

Isle Royale National Park

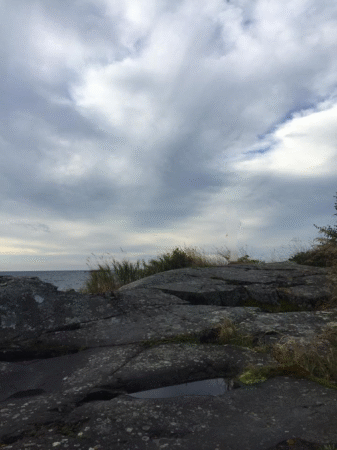

This remote archipelago in Lake Superior is actually the exposed crest of a long volcanic ridge. Its tilted basalt formations, created by ancient lava flows from the rift, stretch for miles underwater. Isle Royale’s copper deposits also trace back to these volcanic events, treasured by Indigenous people for thousands of years.

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

Though famed for its colorful sandstone cliffs, Pictured Rocks sits on the southern edge of the rift system. The stunning rock layers and arches reflect the sedimentary sequences that formed as the rift’s volcanic activity slowed and inland seas flooded the landscape.

Keweenaw Peninsula

Perhaps the most dramatic above-ground evidence of the rift lies here. Over 100 lava flows, known as the Portage Lake Volcanics, are exposed in stacked layers across the peninsula. These rocks hold some of the richest native copper deposits in the world, fueling Michigan’s famed Copper Country.

Lake of the Clouds and the Porcupine Mountains

Located in the western Upper Peninsula, Lake of the Clouds is nestled in a highland shaped by volcanic basalt ridges formed during the Midcontinent Rift. The steep escarpments and rock layers visible along the Escarpment Trail are ancient lava flows, uplifted and exposed by tectonic and glacial forces. Though tranquil now, this landscape is the product of immense geologic drama.

Spiritual Echoes Beneath the Surface

While science explains the rift in terms of plate tectonics and volcanic rock, Indigenous cultures have long recognized and honored the power and mystery of the powerful forces that formed these landscapes through oral tradition and spiritual stories.

Mishipeshu – The Underwater Panther

Among the Anishinaabe people, Mishipeshu, the Underwater Panther, is said to dwell in the deepest parts of Lake Superior. Described as a powerful, horned creature, Mishipeshu is both feared and revered as the guardian of copper and protector of sacred waters.

In some traditions, Mishipeshu controls storms and hides in submerged caverns, portals to other realms. The creature’s presence reflects the indigenous peoples’ understanding of the lake’s awe-inspiring depth and ancient origins, and its connection to copper mirrors the mineral wealth born from the rift.

Nanabozho and the Shaping of the Land

Nanabozho, a cultural hero in Anishinaabe tradition, is credited with shaping the land and waters. According to legend, as Nanabozho traveled across the land, his movements carved out rivers, lakes, and valleys, echoing the real geologic forces that sculpted Michigan’s rift-torn terrain.

These stories remind us that long before science named the Midcontinent Rift, the people of this land understood its power through stories passed across generations, stories that honored the Earth not just as rock, but as a living, moving force.

What It Means

The Midcontinent Rift isn’t just ancient history. It’s the foundation of many of Michigan’s most notable places. From the ridges of the Porcupine Mountains to the cliffs of Pictured Rocks, the rift’s legacy continues to shape how we live, explore, and understand our state. It also connects Michigan to a vast, billion-year-old story, one that predates Pangaea and speaks to the Earth’s ceaseless ability to transform itself.

Sources

- Isle Royale Geology

https://www.nps.gov/articles/nps-geodiversity-atlas-isle-royale-national-park-michigan.htm - Pictured Rocks Geologic Formations.https://www.nps.gov/piro/learn/nature/geologicformations.htm

- Geology of the Keweenaw Peninsula

https://wmich.edu/geologysurvey - Structure and Evolution of the Midcontinent Rift

https://doi.org/10.1002/2013TC003498 - Terms: Gichi-Gami, Nanabozho, Mishipeshu

https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/ - The Canadian Encyclopedia – Mishipeshu |https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/mishipeshu

- Wikipedia – Nanabozho

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanabozho - Wikipedia – Midcontinent Rift System https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midcontinent_Rift_System

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130