Washtenaw Resident Irene Butter Continues to Share Her Holocaust Story and Advocate for Human Rights

By Cynthia Furlong Reynolds

“I didn’t ask to go through the Holocaust, but I was saved through the miracles of luck and the love and determination of my Pappi,” says retired U-M professor Irene Hasenberg Butter, 94. “I learned that I owe it to him and to the others who suffered to talk about what I saw and discuss the lessons of the Holocaust.” Irene is among the last living survivors of Nazi concentration camps. “Suffering never ends, so this work must continue.”

Her story is rife with trauma, drama, persecution, and suffering—as well as miracles, rescues, reconciliation, and redemption. But she wasn’t always willing to share her story.

“When I arrived in Baltimore as a refugee from the camps, I was told it was better if I never spoke of my experiences,” she explains. For thirty years, she only discussed her Holocaust years with her immediate family and fellow survivors. But when she did begin speaking in the 1970s, she soon gained international prominence—and that, in time, led to her reconciliation with the horrors of the past.

Her early years

Born in Berlin, Germany, in 1930, Irene remembers a wonderful childhood—until 1937, when the Nazis confiscated her father’s bank and gave it to “non-Jews.” Ever resourceful, her father managed to find a job with American Express and moved his family to Amsterdam. “But we had not moved far enough,” she says.

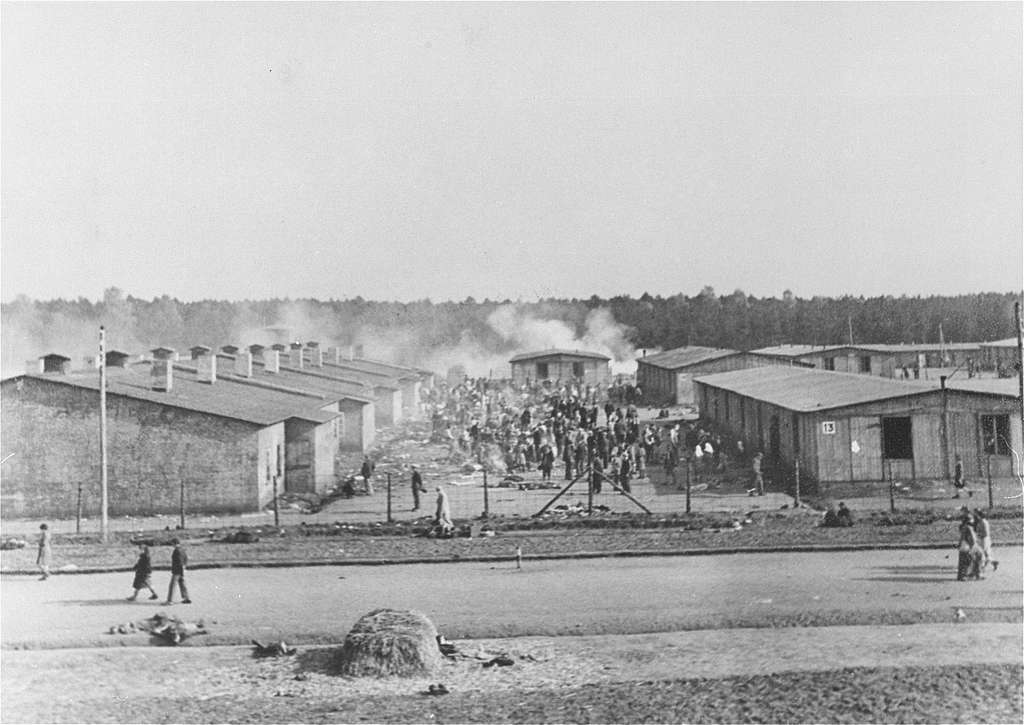

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1940, they instituted the anti-Semitic policies that had caused the Hasenbergs to flee Germany. In 1942, Irene’s grandparents, who had remained in Germany, disappeared into Theresianstadt Ghetto and were never heard from again. Frantically, John Hasenberg contacted sympathetic friends, trying to get visas for his family to leave the Netherlands. Ecuadorian immigration papers arrived at the family’s Amsterdam home in 1943—after Irene, her parents, and brother Werner had been sent to Westerbork transit camp. But miraculously, the postal system actually forwarded the paperwork to them.

“The Germans knew we had no ties to Ecuador, but they needed people to exchange for German citizens in Allied hands,” she says. “Initially, we were treated a little better than some.”

The Hasenbergs struggled against time, hunger, overwork, and Nazi cruelties while continuing to hope they would be released in a trade deal. Although they were able to stay in the transit camp longer than most others, thanks to a sympathetic guard who knew Irene’s father, they were eventually sent to the dreaded Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. There she was briefly reunited with her friend Anne Frank.

”January 1945 was very black for us,” Irene recalls. “Mother was in bed, father was very weak after a brutal beating, and Werner had a serious foot infection.” That’s when Irene’s best friend in the camp, Hanneli Goslat, told her that she had seen Anne Frank there. “We met at the barbed wire fence and learned that she and her sister were very sick and they needed clothes.” The two girls managed to find some clothing to toss over the fence to Anne—“but a woman swooped in and stole them.”

Irene and Hanneli promised to return the following night, but when Irene returned to her parents, the Hasenbergs were informed that, thanks to their Ecuadorian papers, they would leave immediately for Switzerland—if they passed the physical tests. Her father could barely walk and her mother and brother could only move with assistance, but “either by accident or a humanitarian impulse—I’ll never know”—one of the most brutal Nazi guards “mistook” 14-year-old Irene (“I was seventy-eight pounds!) for her invalid mother and allowed the family to board the train.

John Hasenberg died of his injuries two days later, and his body was left at the nearest train station. But Werner, Irene, and their mother crossed into Switzerland and freedom.

“However, the Swiss managed to do what the Nazis couldn’t: they separated my family,” Irene says. Despite her protests, she was sent to a refugee camp in Algiers, North Africa, run by the precursor of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency, while her mother and brother were hospitalized in Switzerland.

When the war ended, a family member in the United States offered to sponsor Irene. She arrived in Baltimore on Christmas Day 1945. Her mother and brother joined her six months later.

The young woman flourished in America. She earned a scholarship to Queens College, became the second woman to earn a Ph.D. from Duke’s department of economics, married, landed a professorship at U-M, and had two children. When her daughter Pamela was in high school, she wrote a paper about the Holocaust and asked her mother to serve as her “visual aide.” “I was surprised at how well that went,” Irene says. From that day onwards, she began speaking publicly about her experiences.

Awards and honors

As her witness became internationally known, a German school invited Irene to visit the campus and speak. Until that time, she had refused to speak in German—in fact, she purposely turned her back on any German speakers. “Their speech reminded me too much of the Nazi guards who screamed at us.” The teacher asked Irene if she would tell her story in German. Irene told her she didn’t think she could. “Just a few German words?” the teacher urged. Irene agreed to try. But when she finished speaking to the students, she realized she had given her entire speech in her native language. “I realized I had broken a barrier. I concluded my resentment.”

Last June, German Ambassador Andreas Michaelis presented Irene Butter with Germany’s highest civilian award, the Officers’ Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany—“comparable to the United States Presidential Medal of Freedom.” The cross reminds Irene of the Iron Cross awarded to her father for bravery during WWI, while he was serving with the German army. “I was very honored to be the second one in our family honored by the German nation,” she says. “It was an act of reconciliation.”

And the awards continue. On March 25, the Netherlands’ Council of State will honor her with the Anne Frank Award for Human Dignity and Tolerance during a ceremony in the Washington, D.C. embassy. This award is particularly poignant because Irene Butter was among the last people to see Anne Frank alive. After the war, Irene learned that Anne died just a day or two after she saw her.

“Anne didn’t live to tell the rest of her story, so I have believed I must do it for her,” Butter says.

Like the Franks, the Hasenbergs were German citizens who fled to the Netherlands when the Nazis confiscated their businesses. The two families were neighbors in Amsterdam until the Nazis invaded that country. The Franks went into hiding, and the Hasenbergs were sent to Westerbork. By 1944, both families were interned at Bergen-Belsen.

“Anne was two years older than I was, and I looked up to her when I was growing up,” Irene says. When The Diary of Anne Frank was published in Dutch in 1947, a friend from Irene’s second grade class in Amsterdam sent her a first edition. Seventy years later, Irene published her own Holocaust memoir, Shores Beyond Shores: From Holocaust to Hope, My Story, which has been translated into four languages. American filmmaker Evelyn Neuhaus made a short documentary film of Irene’s life entitled Never A Bystander.

A commitment to education and peace

The descendants of Holocaust survivors who are members of Temple Beth Emeth, known as the Generations After, have established the Irene Butter Fund for Holocaust and Human Rights Education, to support educational programming about the Holocaust, “and to help address modern challenges “of ‘othering’ and disregard for human rights.” They have just opened an application process for grants to individuals, middle and high schools, community organizations, and faith communities interested in developing exhibits, essay contests, visual art, poetry, music, lectures, and plays based on the Holocaust and human rights themes.

Irene co-founded the Raoul Wallenberg Institute at the U-M, honoring the Swedish diplomat who saved thousands of Jews during World War II. On Martin Luther King Day, the institute sponsored a roundtable discussion addressing the question “Can One Person Make A Difference?” in Rackham Ampitheater.

The retired professor helped establish Zeituna, a local Arab-Jewish dialogue group of women. She has also been recognized for her German podcasts, which are conversations with high school students.

At the age of ninety-four, Irene Hasenberg Butter continues her work, testifying to the worst and best in humanity. “Being a victim at a certain point in your life does not mean that you have to be a victim all your life,” she believes.

SIDEBAR:

Grants are available for holocaust-based educational opportunities

The Irene Butter Fund for Holocaust and Human Rights Education is requesting applications for grants of up to $7,000, to support educational programming that keeps the lessons of the Holocaust alive and addresses modern-day challenges of “othering” and the disregard for human rights.

“Teaching the next generation about the dangers of bigotry and blanket hatred is as important now as it has ever been,” says steering committee chair Regina Lambert-Hayut. The organization is collaborating with the Zekelman Holocaust Center in Farmington and will offer Irene Butter’s memoir to classroom teachers.

Ideas for projects include:

- Developing an exhibit/program (essay, visual art, poetry, music, spoken word) for middle or high school students.

- A speaker series addressing the link between the Holocaust and contemporary antisemitism, racism, authoritarianism, and human rights abuses.

- Developing interfaith youth ambassadors with knowledge of the Holocaust.

- A residency by a scholar, poet, or musician on the topic of Holocaust and human rights education.

The fund will cover the purchase of materials and field trips to the Zekelman Holocaust Center. Proposal deadline is March 1, but applicants are encouraged to submit a one-page letter of intent to apply by February 15.

For additional information, visit https://www.jewishannarbor.org/apply-irene-butter-fund-for-holocaust-and-human-rights-education or contact Rita Benn at [email protected].

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130