In the heart of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, GPS collars, drones, and field research are revealing new insights into the lives and deaths of one of the region’s most iconic animals – the moose.

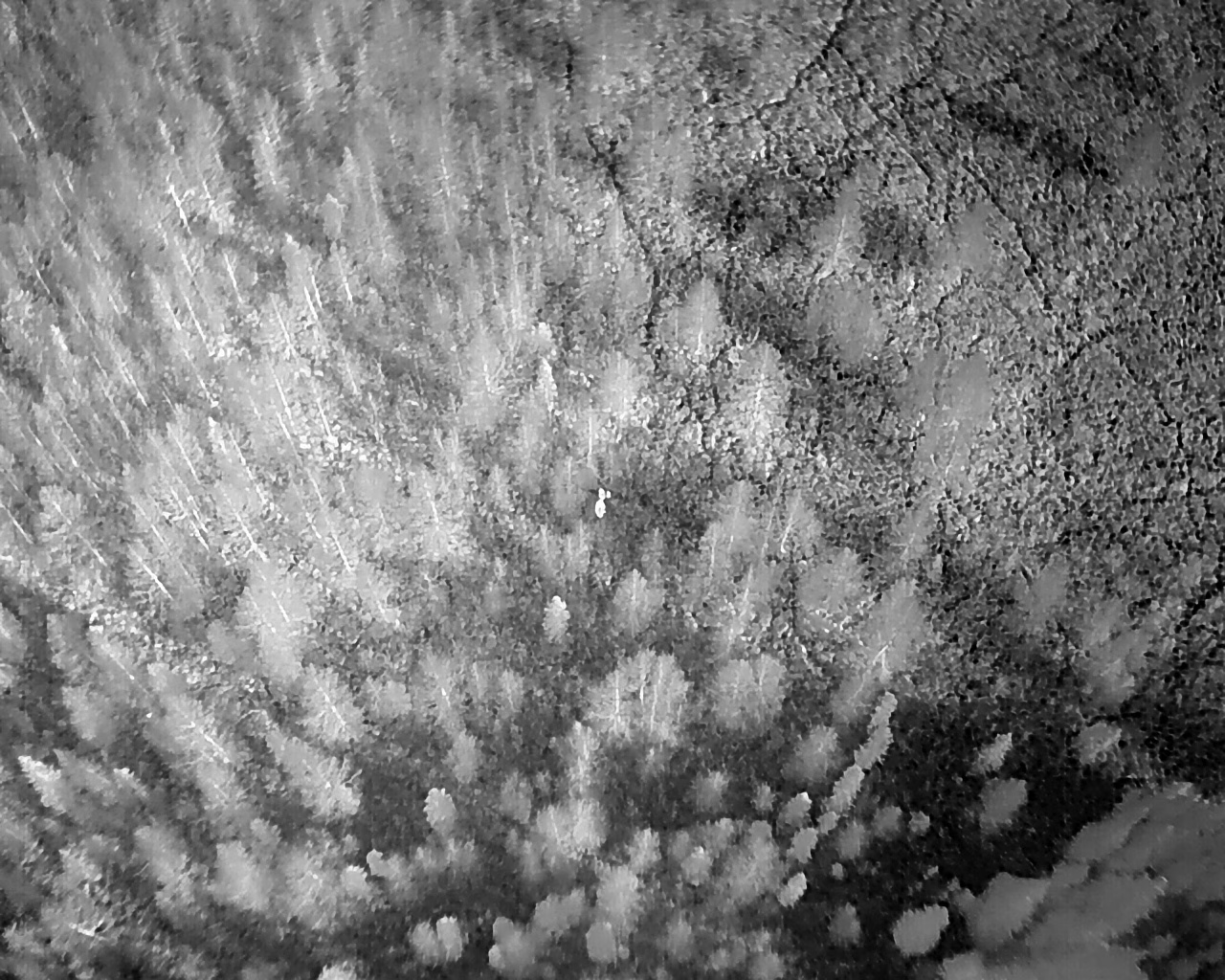

Photo: A collared cow moose nurses her calf in the western Upper Peninsula. This photo, captured using high-powered zoom from a drone flying more than 300 feet above, offers a rare, hands-off glimpse into the first days of a calf’s life. Photo courtesy of DNR.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has confirmed the first case of wolf predation on a moose calf born to one of the collared females in its most extensive moose study to date. Launched in February 2025, the research aims to uncover why Michigan’s moose population isn’t growing, despite suitable habitat and long-standing conservation efforts in the Upper Peninsula.

Conducted in collaboration with the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community and Northern Michigan University, the study uses GPS collars and heat-sensing drones to track 20 adult moose across rugged northern terrain. So far, researchers have collected more than 50,000 GPS data points, offering an unprecedented view of how these massive herbivores move, mate, and survive in the wild.

In the last two weeks, six of the ten collared female moose gave birth to a total of nine calves, three single births and three sets of twins. By monitoring step counts and movement patterns, researchers could detect signs of labor and then deploy drones to confirm births, capturing thermal images of the mothers and their young nestled in the woods.

However, the research also focuses on mortality. Two of the collared calves have already died. One, a female, suffered fatal trauma, with a necropsy revealing cranial injuries but no evidence of a vehicle collision or attack. Moose are known more for their size than agility, and injuries from falls or rough terrain are not uncommon.

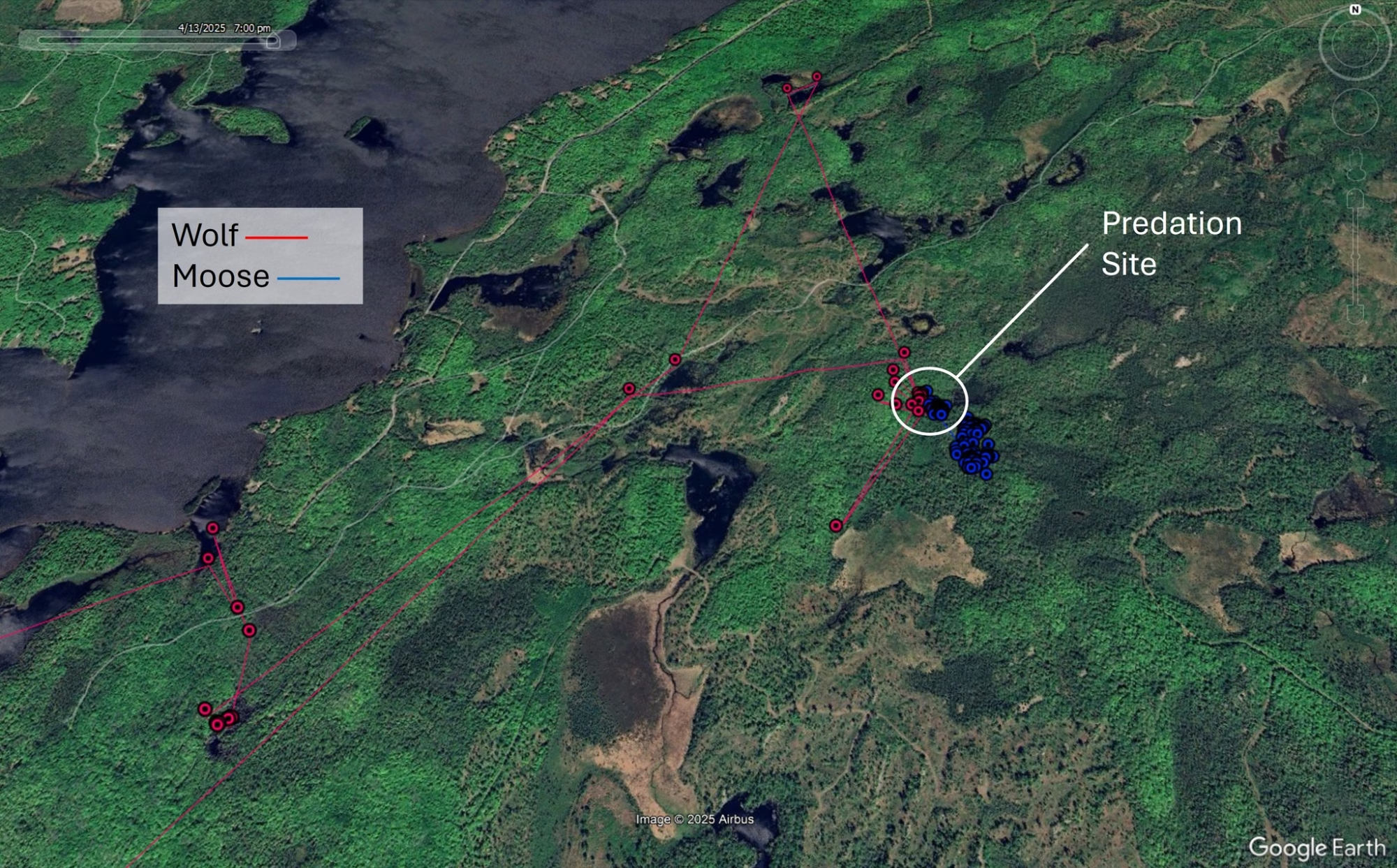

The second calf, a male, was found dead in a stream, with bite marks consistent with a wolf attack. By comparing the calf’s GPS movements with those of nearby collared wolves, researchers found that an adult female wolf had been at the same location at the same time as the calf, confirming the cause of death as predation. This marks the first confirmed wolf kill of the study and helps build a clearer picture of predator-prey dynamics in the region.

As interest grows in wildlife across the Great Lakes, many are asking: Are there wolves in Michigan? The answer is yes, particularly in the U.P., where gray wolves have established packs and play a significant ecological role. Their presence and impact on moose, deer, and other species are an essential part of ongoing research.

This development is an important milestone for the study, which seeks to understand not only reproduction rates but also the leading causes of moose mortality. Understanding how wolves, environmental factors, and habitat changes affect moose survival could eventually shape conservation efforts and wildlife management policy in Michigan.

For now, the team continues to monitor the remaining moose and their offspring as summer progresses. With more data still coming in, the project aims to deepen understanding of how moose function within Michigan’s northern ecosystems, one GPS ping at a time.

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130

8123 Main St Suite 200 Dexter, MI 48130